Back to School

Paul's Commentary #22 by Paul Francis, September 9, 2025

In memory of Jim Tallon (1941-2024), who served in the New York State Assembly for 19 years, including as majority leader and chair of the Assembly Health Committee, on the New York State Board of Regents from 2002 to 2017, and as the president of the United Hospital Fund from 1993 to 2017.

Introduction

Last week, nearly all of New York State’s 2.4 million students in grades K-12 returned to school. In New York City, which is the nation’s largest public school system, approximately 800,000 students returned to New York City’s district schools, another 145,000 students returned to New York City’s charter schools, and another 200,000 or so students returned to nonpublic schools, including religious and private schools.

The Back to School season led me to ponder a public policy paradox that has interested me for some time. That paradox is the divergent trajectories of the healthcare sector and the education sector in the United States over the last several decades – especially in the last decade. Healthcare and education arguably are the two most important sectors in American life: both sectors engage nearly every American at some point in their lives, are massive in size, and are heavily influenced by both governmental policies and societal change.

There has been a lot of progress in health and healthcare over the last three decades, while the trends for education are mostly going in the other direction. If you were to chart them in a time series, health/healthcare would be up and to the right, while the trend line for education would be further down and to the right with each passing year.

I think the evidence is clear that developments in medicine and healthcare technology, widely expanded government funding for healthcare coverage, and societal changes such as reductions in smoking, common childhood vaccination requirements, fluoridated drinking water, and other public health initiatives have resulted in significant changes in how healthcare is delivered and significant improvements in most measures of health conditions and outcomes over the last few decades.

Over the same period of time, there has been a striking lack of change in how education is delivered and a marked decline in student achievement, as well as a growing disengagement with the educational system that is reflected in both rising chronic absenteeism (defined as missing more than 10% of class time) and the rise of alternatives to traditional public schools. These trends are more the result of economic, social, and cultural factors than they are of the educational system itself. But the fact remains that the educational system is failing in its mission to improve the competency of students.

Demographic changes have also affected both the health and education sectors, with increasing demands on the healthcare system because of the aging of the population, and dramatic declines in the number of school-age children as a percentage of the total population because of declines in birth rates. In 1990, the number of K-12 students in the United States was 46.2 million, or roughly 18.5% of the US population. By 2024, the number of K-12 students in the United States was 49.5 million, which represented roughly 14.5% of the US population. Although total enrollment in K-12 schools is higher today than it was in 1990, in the last decade, there has been a decline in the absolute numbers of school-age children. For example, enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools in New York State declined 7.3% between 2013 and 2023.

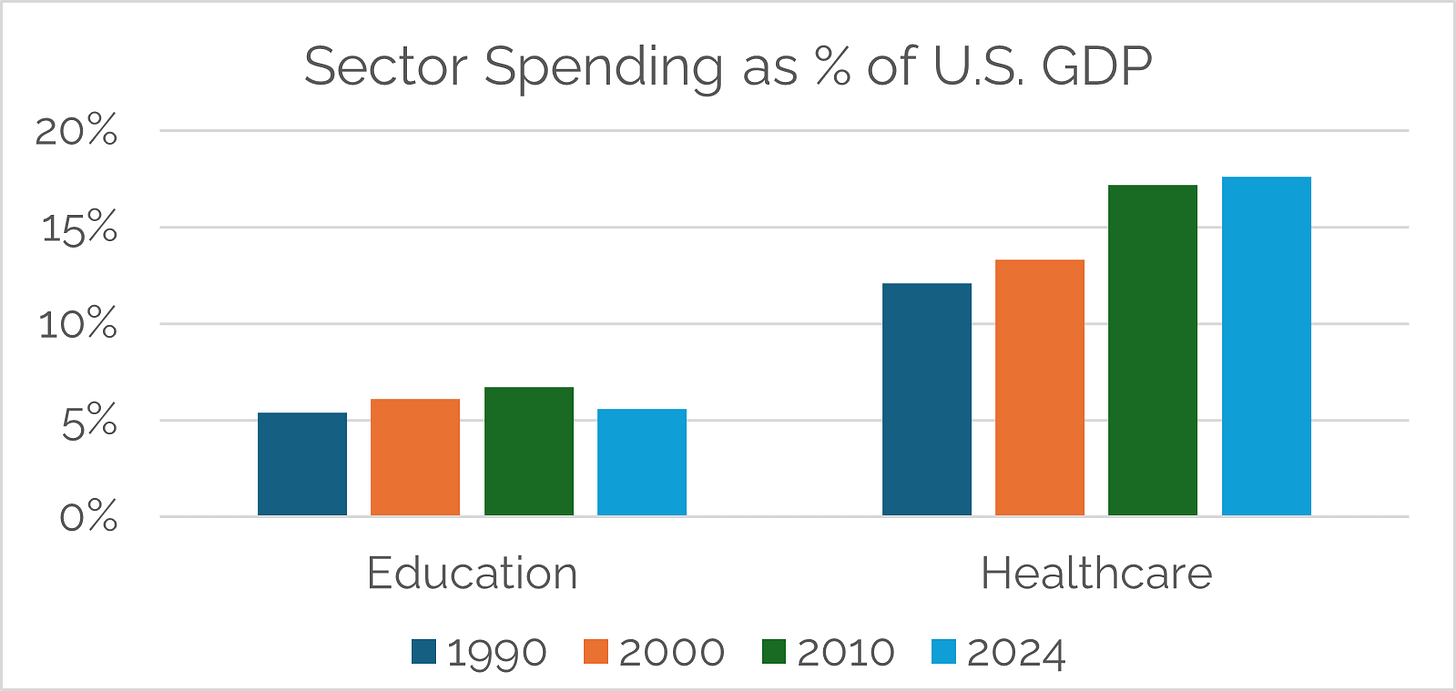

Irrespective of whether it is a matter of causation or correlation, there has also been a divergence in the amount society spends on healthcare versus education. Total national health expenditures rose much more dramatically, from 12.2% of GNP/GDP in 1992 to roughly 18% of GNP/GDP in 2024. Nominal spending on healthcare increased at a compound annual growth rate of approximately 6% since 1990.

Despite the slower rate of growth in the number of students enrolled in K-12, total spending on K-12 education nationally stayed roughly flat between 1990 and 2024 as a percentage of GNP/GDP at approximately 5%, as shown in the chart below, while nominal per-student spending grew at a rate of approximately 4.3% per year.

It begs the question of whether educational outcomes would be better if spending on education had kept pace with the rate of growth of GNP/GDP, much less the rate of growth of healthcare expenditures. Instead, society has reduced the share of the nation’s economic output spent on education, as opposed to increasing the percentage for healthcare.

Many would scoff at the idea that the major problem with education is that we don’t spend enough money on it. After all, the United States spends more on education as a percentage of GDP than its OECD peers, at least when higher education is included. And New York, for example, has the highest per-student spending in the country with middle-of-the-pack results.

It may well be true that marginal increases in education spending without other structural changes would not materially alter outcomes, but it is a worthwhile thought experiment to ask what education would look like today if the rate of spending growth on education had matched that of healthcare. The sector might have been able to attract and retain a different caliber of teachers—by, like some OECD peers, paying teachers closer to the salaries for other graduate school-educated workers— while supporting early childhood education, operating facilities that better support non-core subjects such as art, music, and physical education, and being better equipped to address rapidly growing mental health and behavioral challenges, among other factors that hinder good outcomes in education.

The remainder of this commentary tests my central thesis against the empirical evidence about the state of the health and education sectors and addresses at a high level what many people regard as the reasons for the diverging trajectories of health and education. I conclude with my speculation about what the sectors might look like in 10 years’ time.

There is a small cottage industry of experts writing about the future of education and healthcare. You can find many thoughtful pieces on these issues in both the mainstream media and the world of podcasts and Substack essays. Among many, many examples about education, see the 2024 New Yorker article, “The Death of School 10: How declining enrollment is threatening the future of American public education,” and the Free Press essay, “The War on Knowledge,” published on August 31, 2025.

When it comes to health and healthcare, among many examples, take a look at Dr. Eric Topol’s Substack called Ground Truths, which describes on a weekly basis what often seems like miraculous progress in medicine and healthcare technology.

Progress in health and healthcare over the last three decades

Health and healthcare are subject to a wide range of quality, outcomes, and performance metrics. While the education sector has moved away from prioritizing standardized metrics, the health and healthcare sector continues to embrace metrics at an ever-increasing level of granularity.

By “health”, I am referring to health outcomes, which can be understood through population health measures. “Healthcare,” as I use the term, refers to the performance of the healthcare delivery system. HEDIS (which stands for Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set) measures are a standardized set of performance measures used widely in the United States to evaluate the quality of care and services delivered by healthcare providers and insurance plans.

Critics of the US healthcare system challenge the central premise that health outcomes have improved. The MAHA movement makes these charges in such a vehement and largely unscientific (if not anti-scientific) way that it is easy to dismiss. However, some sophisticated public health practitioners referred to what they describe as the “Third Epidemiologic Transition,” which is marked by a shift from often more visible infectious disease burden and mortality to increased chronic/noncommunicable disease prevalence, as well as slowing birth rates and a declining rate of improvement in mortality rates.

In terms of the healthcare delivery system, there is a significant body of work focused on the extent to which the U.S.’s healthcare system is found wanting compared to other countries. The Commonwealth Fund’s Mirror, Mirror 2024: A Portrait of the Failing U.S. Health System, Comparing Performance in 10 Nations, Peterson-KFF’s How does the quality of the U.S. health system compare to other countries?, and Ezekiel Emanuel’s Which Country has the World’s Best Health Care?, to name just a few. These sources compare health systems’ performance with measures such as access to care, care process, administrative efficiency, equity, and health outcomes between countries.

It is true that there has been a dramatic increase in the percentage of American adults with at least one chronic disease – from roughly 45% in 1987 to roughly 76.4% in 2023. Approximately half of Americans currently experience two or more chronic diseases, and an estimated 12% have five or more chronic conditions. Among other negative indicators, overdose-related mortality grew exponentially, from a rate of approximately 3.4 per 100,000 in 1990 to 32.4 per 100,000 in 2021, while the percentage of adults estimated to have any mental illness has grown from approximately 17.7% in 2008 to approximately 23% in 2022.

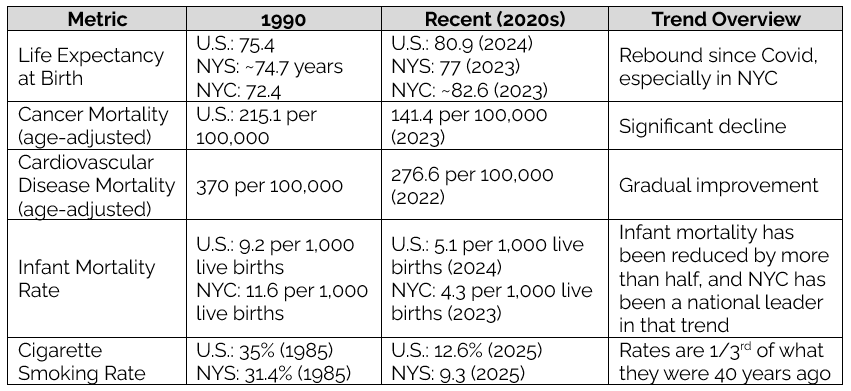

Despite these negative developments in certain areas and continuing racial disparities, the improvement in the overall level of health and the effectiveness of healthcare delivery is supported by the most absolute measures of population health. There is such a wide range of standardized health outcome metrics that it is a subjective process to curate the most important. I have chosen to look at the following set of metrics: life expectancy, premature mortality, infant mortality, as well as mortality due to two significant causes of death – cancer and cardiovascular conditions.

The table below summarizes these trends:

In terms of the causes of these improvements in health outcomes, it is a truism in health that clinical treatment accounts for a relatively small percentage of health outcomes. Public health efforts, which receive a tiny fraction of what is spent on clinical care, are more impactful, along with other investments in so-called social determinants of health. For example, reduction in smoking rates by two-thirds over the last several decades, as a result of consistent public messaging, smoke-free laws, and increased taxes on cigarettes, has had a tremendous positive impact on healthcare outcomes over the same period.

Even if public health initiatives and resulting behavior changes had a greater aggregate impact on the improvement of health outcomes, it is undeniable that there have been dramatic advances in medicine and medical devices over the last three decades which have reduced mortality and morbidity while generating efficiencies such as shorter lengths of stay in hospitals and greatly expanded ability to perform procedures outside of an inpatient setting. Statins, antihypertensives, cancer immunotherapies, and antivirals reduced mortality from their corresponding conditions, while imaging, minimally invasive surgery, and critical care advances improved survival and recovery.

Delivery system reforms have also led to improved healthcare performance. Electronic health records improved coordination, while quality improvement initiatives, such as readmissions penalties, pushed hospitals to improve outcomes. Safer treatments and expanded outpatient care made shorter hospital stays possible, increasing efficiency while improving health outcomes.

Finally, when discussing improvements in health and healthcare, it’s important to acknowledge the significant increase in society’s investment in healthcare services, as measured by the growth of national health expenditures as a percentage of GNP/GDP. Moreover, government-funded health care coverage expanded considerably over these years through health insurance coverage programs backed by a series of massive federal investments. The Children’s Health Insurance Plus Program (CHIP) in 1997, Medicare Part D coverage in 2003, and the Affordable Care Act in 2010 greatly reduced financial barriers to people receiving care.

Regression of educational outcomes over the last several decades

The core metric of education is competency in literacy and mathematics. This is not to suggest that producing competency is the only purpose of schools. As noted by the education expert, Rebecca Winthrop:

“Kids are learning all sorts of things in a classroom. They’re learning how to self-regulate emotions in a group. They’re learning how to understand different perspectives from kids who are different from themselves. They’re learning how to ask for help when they need it.”

“We Have to Really Rethink the Purpose of Education,” Ezra Klein podcast with Rebecca Winthrop, New York Times transcript, May 13, 2025.

But competency in literacy and mathematics is the necessary, if not sufficient, condition of being educated.

By many measures, these competency metrics are going in the wrong direction. Evidence of the decline in educational outcomes is not limited to declining NAEP (National Assessment of Educational Progress) scores and sharply increased rates of chronic absenteeism. The marked decline in literacy and mathematics has contributed to a measurable decline in IQs in the developed world as a whole. Indeed, there has been a striking decline in reading at even the most elite educational institutions, as described in the widely read article “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books,” by Rose Horowitch in The Atlantic on October 1, 2024.

This is a worldwide phenomenon, so not just an indictment of the US educational system. As Sarah O’Connor, in the Financial Times, wrote last December:

This month, the OECD released the results of a vast exercise: in-person assessments of the literacy, numeracy and problem-solving skills of 160,000 adults aged 16-65 in 31 different countries and economies. Compared with the last set of assessments a decade earlier, the trends in literacy skills were striking. Proficiency improved significantly in only two countries (Finland and Denmark), remained stable in 14, and declined significantly in 11, with the biggest deterioration in Korea, Lithuania, New Zealand and Poland.

Among adults with tertiary-level education (such as university graduates), literacy proficiency fell in 13 countries and only increased in Finland, while nearly all countries and economies experienced declines in literacy proficiency among adults with below upper secondary education. Singapore and the US had the biggest inequalities in both literacy and numeracy.

“Thirty per cent of Americans read at a level that you would expect from a 10-year-old child,” Andreas Schleicher, director for education and skills at the OECD, told me — referring to the proportion of people in the US who scored level 1 or below in literacy. “It is actually hard to imagine — that every third person you meet on the street has difficulties reading even simple things.

“Are We Becoming a Post-Literate Society?,” by Sarah O’Connor, Financial Times, December 26, 2024.

The decline in educational outcomes appears to be accompanied by a gradual reduction in intelligence as measured by IQ scores. A landmark 2023 study from Northwestern University and the University of Oregon described what it called a “reverse Flynn effect” in recent years in the United States. The original phenomenon known as the Flynn Effect was that IQ scores substantially increased from 1932 through the 20th century, with differences ranging from three to five IQ points per decade. But, as summarized in the publication Campus Reform:

[A] new study from Northwestern University has found evidence of a reverse “Flynn effect” in a large U.S. sample between 2006 and 2018 in every category except one. For the reverse Flynn effect, there were consistent negative slopes for three out of the four cognitive domains.

Ability scores of verbal reasoning (logic, vocabulary), matrix reasoning (visual problem solving, analogies), and letter and number series (computational/mathematical) dropped during the study period, but scores of 3D rotation (spatial reasoning) generally increased from 2011 to 2018, the study found. Composite ability scores (single scores derived from multiple pieces of information) were also lower for more recent samples. The differences in scores were present regardless of age, education or gender.

The professors who authored the study theorize that the quality of education could play a role in reversing the IQ gains enjoyed by previous generations….

Overall declines held true across age groups after controlling for educational attainment and gender, but the study shows that the loss in cognitive abilities is steeper for younger participants. “[T]he greatest differences in annual scores were observed for 18- to 22-year-olds,” the authors write.

“[T]his might suggest,” they continue, “that either the caliber of education has decreased across this study’s sample and/or that there has been a shift in the perceived value of certain cognitive skills.”

“Historic Decline in IQ Could Stem from Poor Education, Study Shows,” by Shelby Kearns, Campus Reform, March 8, 2023

These negative trends almost certainly are less the result of shortcomings in the current education system than behavioral changes wrought by the “Attention Economy” – i.e., competing, modern sources of distraction represented by “screen time,” social media, and “aural” platforms such as podcasts, YouTube, and TikTok.

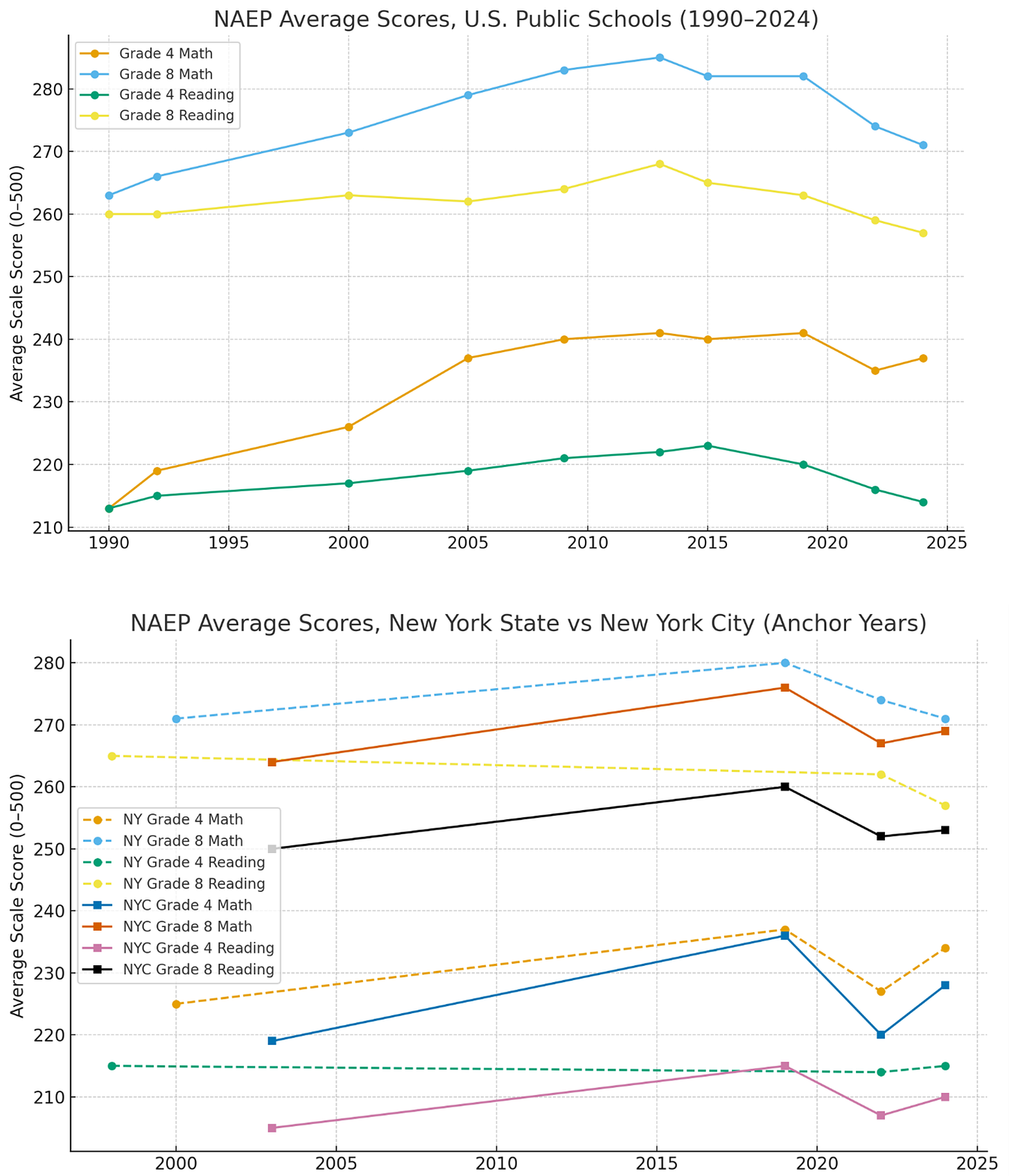

The NAEP test has been administered by the National Center for Education Statistics since the 1960s. The tests are given periodically to samples of students in grades 4 and 8 to measure their competency in reading and math. The results are reported on a scale scored from 0 to 500 for reading and math, which makes it possible to track trends over time.

As reflected in the charts below for the US, New York City, and New York State, the story the NAEP scores tell is that the nation made steady progress for two decades beginning in 1990, then plateaued or showed slight declines in the 2010s, followed by a sharp decline in the Covid era. This decline since the Covid era has given back a decade or more of progress, leaving educational outcomes about where they were in the year 2000. There has been some recovery in the last two years from the depths of Covid, but NAEP scores today are still roughly flat to 2010 levels.

Some education researchers ascribe the plateauing of results around 2010 at least in part to the retreat from the “standards” movement. The accountability- and standards-based reforms, including state testing systems, No Child Left Behind mandates, and math curriculum reforms, that had fueled earlier gains delivered their biggest impact in the 1990s and 2000s, but by around 2013, the returns had diminished.

At the same time, classroom conditions and student engagement were leveling off: instructional time wasn’t growing, and chronic absenteeism was beginning to rise even before the pandemic. Socioeconomic factors mattered too—inequality and the aftereffects of the 2008 recession created headwinds for students in high-need schools. Added to this, screen time and digital distractions were affecting reading stamina and attention, both in the classroom and at home.

The arrival of Covid in 2020 severely disrupted education with widespread school closures and the need to shift to remote learning. When schools reopened, student attendance collapsed: in the 2021–2022 school year, nearly one in three students nationwide was chronically absent – defined as missing at least 10% of school days. This loss of learning time hit math hardest, but reading scores also fell to their lowest levels in decades. Recovery from the Covid dip has been hampered by teacher shortages, a significant increase in student misbehavior (that is exacerbated by mental health challenges), and growth in chronic absenteeism (especially in high-need areas).

In short, the educational system has been unable to adapt to broader societal changes and continue to make progress in educational outcomes as it did between roughly 1990 and 2010. It is ironic that technology, which accounts for many positive developments in healthcare, has had the opposite effect in education, with the digital distractions of the Attention Economy impeding reading and learning at all levels. Now, the education sector faces a new risk from generative AI. Despite AI’s potential for good, the technology’s effect is too susceptible to being a crutch through cheating, which threatens to further erode the learning process.

The effect of government policy and delivery system structure

Both government policies and contrasting delivery system structures of healthcare and education have contributed to the divergent trends in these two sectors.

Looking first at healthcare, the last 35 years saw a pronounced increase in government-funded healthcare coverage. The percentage of Americans aged 19-64 without healthcare coverage decreased from about 12% in 1990 to about 8% percent in 2023. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) and ACA Medicaid expansion collectively provided coverage to almost 43 million Americans in 2024. At a time when total national health expenditures grew at a compound annual rate of 6%, the share of total national health expenditures accounted for by the federal, state, and local governments increased from 27% in 1990 to 48% in 2023, with governmental spending increasing at a compound annual growth rate of 6.7%.

As described above, public-health interventions such as antismoking policies, support for medical research through the National Institutes of Health, and governmental reimbursement policies that supported the adoption of health innovations all contributed to the overall improvement in population health outcome measures.

The structure of the healthcare delivery system is shaped in part by governmental policies. I would argue that the pluralistic and competitive structure of the healthcare delivery system also contributed to progress in healthcare delivery and improved health outcomes. For example, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) created incentives through value-based purchasing and penalties/bonuses tied to measurable outcomes (e.g., Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP)), and HITECH incentives rapidly diffused electronic health records, enabling quality measurement and care coordination. The overall effect was to align dollars with measurable results, something education initiatives rarely manage at scale.

The distributed and competitive nature of healthcare providers, combined with consumer choice, has also contributed to improvements in the healthcare delivery system, as health systems compete for patients based on both consumer satisfaction and outcome quality measures. Patients vote with their feet. By contrast, governmental policies blocking reform and the relatively monolithic structure of the education system have contributed to the lack of progress in education.

Governmental funding for innovation also differs significantly between the healthcare and education sectors. For example, the HITECH Act in 2009 authorized approximately $25.9 billion to promote health information technology, while CMS made another $22.5 billion available to providers to adopt the “meaningful use” of electronic health records. By contrast, the Race to the Top initiative, launched under President Obama in 2009, was a competitive grant program that invested about $4.4 billion to support education reforms such as adopting standards, data systems, teacher evaluation, and school turnaround efforts.

School district policies over the last 35 years regarding how reading is taught are now thought to have unintentionally harmed educational outcomes. The 20th-century “Reading Wars” pitted phonics (sounding out words) against whole-language/balanced literacy (cueing, meaning-first, guessing). As described in a recent article in The Atlantic:

“Teachers had fallen for a single, unscientific idea—and that its persistence was holding back American literacy. The idea was that “beginning readers don’t have to sound out words.” That meant teachers were no longer encouraging early learners to use phonics to decode a new word—to say cuh-ah-tuh for “cat,” and so on. Instead, children were expected to figure out the word from the first letter, context clues, or nearby illustrations. But this “cueing” system was not working for large numbers of children, leaving them floundering and frustrated. The result was a reading crisis in America.”

“How One Woman Became the Scapegoat for America’s Reading Crisis,” by Helen Lewis, The Atlantic, December 2024.

Over the last decade, 40 states and the District of Columbia have passed laws intended to replace balanced literacy with more phonics-driven models. New York City has adopted a phonics-based model called NYC Reads. Mississippi has attracted much interest and praise since adopting its Literacy-Based Promotion Act in 2013. Mississippi students were performing a full grade level below their peers around the country as recently as 2013, but by 2024, they were performing nearly half a grade level above the average U.S. student.

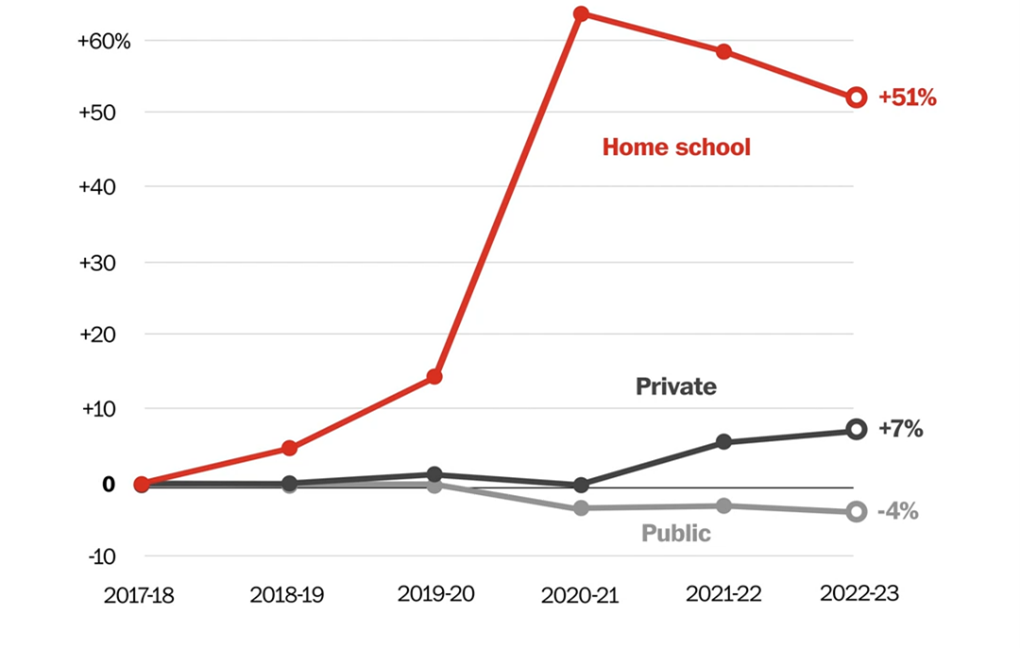

More fundamentally, although K-12 education is regulated by the states and controlled by local school boards, compared to healthcare, public education is delivered in a monolithic system with limits on innovation imposed by union contracts and generally seeks to limit school choice. Twenty years ago, the education reform initiative with the most energy was charter schools. Now, the energy is behind school choice vouchers and homeschooling.

The following chart from the Washington Post illustrates the explosive growth of homeschooling in recent years, although it started from a very low base. The overall enrollment figures as of 2022-23 were still weighted heavily to traditional public schools: Public Schools (~49M), Charter (~3.7M), Catholic (~1.7M), Homeschooling (~2.3M).

Since 2023, states such as Georgia, Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina have passed new or expanded voucher laws, with 15 states having some kind of voucher program. Florida’s program now costs nearly $3.9 billion annually.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act included an unlimited tax credit program that provides a new federal, dollar-for-dollar tax credit – up to $1,700 per taxpayer – for donations to scholarship-granting organizations that fund private school scholarships or support homeschooling.

Although there might be some wiggle room in the interpretation, the clear intention of the law is to exclude funds from being used to benefit public schools or public school foundations. The bill requires individual states to opt in to the law in order for their residents to take advantage of the tax credit. In Albany parlance, this requirement is clearly designed to “jam” Blue state governors. Opting in is likely to be fiercely opposed by teachers unions and public school advocates, while at the same time, backers of religious and independent schools will be incensed if a state walks away from what is essentially free federal money.

Where will we go from here?

As Yogi Berra said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” What makes predictions about the world 10 years from now particularly confounding is the wide range of opinions about the potential functionality and pace of adoption of artificial intelligence. It might seem hyperbolic when the CEO of Google says that “AI has the potential to be more transformative than electricity or fire.” But a serious and sober person like Reid Hoffman says, “AI is going to reshape every industry and every job,” while Bill Gates says that “great medical advice [and] great tutoring” will become free and commonplace. Others are more skeptical, arguing that the potential of large language models is exaggerated.

I tend to side with the AI “optimists” when it comes to the potential functionality of AI and clearly side with the “pessimists” when it comes to the unfortunate – even dystopian – implications of a world in which AI and AI-powered robotics can perform most jobs as well or better than human beings. On balance, and looking out 10 years, I think we should expect the impact of AI and other technological change in healthcare and education to look something like the following:

Artificial intelligence and robotics will transform healthcare in the years to come. Humanoid robotics – probably but not certainly – will solve society’s most intractable fiscal problem, which is the cost of home and personal care for a rapidly aging population. The pace of adoption of the full potential of AI in other areas will be less a matter of functionality and more a question of restraints on change that will be imposed by regulation, which reflects both the paternalistic impulses of healthcare and a guild mentality among providers. The extent of improvements in health outcomes will be more a function of the ability of AI and other new technologies to positively impact social determinants of health, as well as the extent to which society is able to mitigate the negative human impacts that will accompany the disruption of AI and robotics.

I wish I had a stronger conviction about the impact of AI (and other technology) on education. The mainstream conventional wisdom was expressed by Bill Gates as follows in a post after his interview with the education innovator Sal Kahn:

“AI tools and tutors never can and never should replace teachers. … With every transformative innovation, there are fears of machines taking jobs. But when it comes to education, I agree with Sal: AI tools and tutors never can and never should replace teachers. What AI can do, though, is support and empower them.”

AI optimists suggest the changes will be more fundamental as every student in the world has a free tutor who can provide individualized instruction with more knowledge than any human being. If AI works well for 30% of students who are already engaged but doesn’t change the educational experience for the 70% who are not, it will exacerbate the existing divide in education.

We’ll see. As with healthcare, the pace of adoption of AI and the extent of change will be significantly affected by regulation and protection of vested interests (for better or worse). This may lead to a further fragmentation of the education system. Recently, there has been a lot of buzz around a new private school chain called Alpha, which covers core subjects using AI without teachers for two hours a day and reserves the rest of the day for non-traditional education.

The risks of AI for children are almost incalculable. If predictions that in 10 years every child will have an AI friend come to pass, educational performance may seem beside the point. On balance, I do think that AI will improve educational outcomes, but how much will depend on how well we address the “social determinants of education,” as well as our ability to overcome the corrosive effects of the Attention Economy and AI cheating that makes the technology a crutch instead of a tool.

I think a third major trend 10 years from now will be considerably more consumer empowerment and choice in both healthcare and education. Consumer empowerment is resisted now in healthcare primarily by the paternalistic tendencies of healthcare regulation and the guild behavior of providers. Eventually, those will be overcome by consumers’ desire and ability to have more control over their healthcare.

In education, the public school monopoly will give way – for better and for worse – to a more pluralistic and fragmented system. I am a huge believer in the importance of a common experience and public schools for the social fabric of our nation. But if the public school monopoly cannot find ways to enable more diversity of experience than is the case today, it will eventually be significantly displaced by more individualized solutions that offer more choices to parents and students.