Improving New York’s infrastructure for health data, information, and analysis is one of the core focuses of the Step Two Policy Project. Our first Policy Brief in this area, titled Democratization of Health Data, Information and Policy Analysis, compared the general opacity of health data and information in New York to the robust infrastructure in Massachusetts. The paper argued that a prerequisite to effectively restructuring the healthcare delivery system in New York was a level of transparency that would enable policymakers and health stakeholders to better understand the system as it exists today so that we could chart a better course for the future.

We received a good deal of positive feedback from stakeholders who have long been frustrated that much of the New York data and information in the related areas of health, behavioral health, and human services are difficult to access or completely opaque to the public. We also realize, however, that the discussion of this issue would benefit from further clarification about what we mean by “health data and information.”

A threshold clarification we need to make is that “health data and information” is not limited to the health care delivery system and public health data reported to the New York State Department of Health (NYS DOH). Every important trend in healthcare points to the importance of the integration of the silos of physical health, behavioral health (i.e., mental health, substance use disorders, and services for people with developmental disabilities), and – increasingly – human services that address social determinants of health. This means that related data and information must also be integrated to present a comprehensive picture.

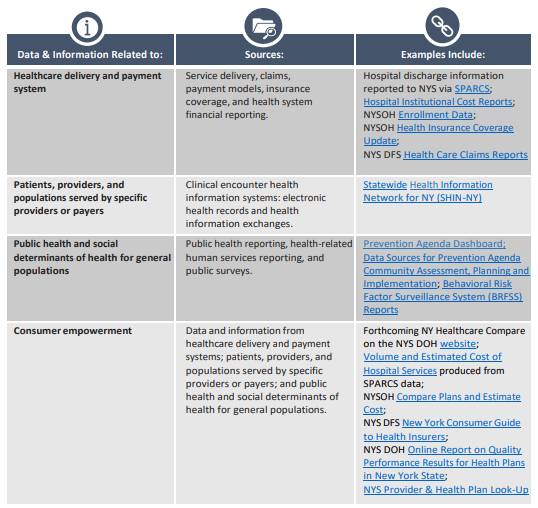

Another important clarification is that “physical health, behavioral health, and health-related human services data and information” is an umbrella term that covers such a wide range of sources and uses of data and information that it is helpful to separate this broad universe into various categories. Such a categorization is a subjective exercise, and there may be better ways to define the different categories. That said, we think of “health data and information” as falling within at least four distinct categories. These include data and information related to:

the healthcare delivery and payment system, as captured through service delivery, claims, payment models, insurance coverage, and health system financial reporting;

patients, providers, and populations served by specific providers or payers, as captured through clinical encounter health information systems such as electronic health records and health information exchange networks;

public health and social determinants of health for general populations, as captured through public health reporting, health-related human services reporting, and public surveys; and

consumer-facing, consumer empowerment platforms, such as those related to price transparency, individual cost-sharing, and provider accessibility.

The categories are summarized in the following graphic representation:

The descriptions set forth in more detail below convey the differences between these types of data and information, each of which serves a related but distinct purpose.

Data and Information Related to the Healthcare Delivery and Payment System

Our Policy Brief, Democratization of Health Data, Information, and Policy Analysis focused primarily on the first of these categories –infrastructure to support data and information related to the healthcare delivery and payment system. It is important to emphasize that the healthcare delivery system includes not only physical health but behavioral health, health-related human services information (such as access to healthy food and supportive housing) related to the social determinants of health, and important data related to insurance claims, payment models, and insurance coverage.

Health data and information related to the healthcare delivery system are the principal types of data and information reported on by the Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis (CHIA). CHIA’s most recent annual report is titled Annual Report on the Performance of the Massachusetts Health Care System (March 2023). The table of contents of the Annual Report illustrates the type of health data and information related to the healthcare delivery and payment system, specifically:

Total healthcare expenditures

Private and public insurance enrollment

Provider and health systems trends

Quality of care in the Commonwealth

Total medical expenses and alternative payment methods

Private commercial contract enrollment

Private commercial premiums

Private commercial member cost-sharing

Private commercial payer use of funds

Under these broad topic headings, the CHIA Annual Report includes information about primary care and behavioral healthcare expenditures, metrics regarding prescription drugs, relative price and provider price variation (an important healthcare delivery system measure that New York presently doesn’t calculate), hospital financial performance, and insurance coverage. CHIA utilizes an integrated data set that combines hospital financial data with a variety of other CHIA data sets, such as payer mix, utilization, and hospital characteristics (much of the content of these other data sets is captured in the Massachusetts All-Payer Claims Database, as well as in New York’s All Payer Database, which includes SPARCS as a source).

Another good presentation of the health data and information related to the healthcare delivery system is the CHIA Standard Statistics. The CHIA Standard Statistics include such important delivery system information as the number of statewide inpatient discharges, most frequent inpatient discharges by diagnosis related group, emergency department visits, and the unplanned readmission rate, and these statistics are presented in a regular and comparable way.

The CHIA Hospital Profiles provide a view of the healthcare delivery system through the lens of individuals facilities. Through retrospective payer- and provider-submitted data sources, including relative price data, hospitals’ audited financial statements, cost reports, and discharge data, the Profiles provide descriptive and comparative information on acute and non-acute hospitals based on hospital characteristics, services, payer mix, utilization trends, cost trends, and financial performance over a five-year period. Hospital Profiles also include an interactive dashboard with data visualizations to offer additional insight into the acute hospital industry statewide.

In aggregate, the data and information presented by CHIA provide a coherent and reasonably comprehensive picture of the healthcare delivery system in Massachusetts. Policymakers and stakeholders who seek to influence policy are probably the primary audience for this type of data and information. The CHIA data and information taxonomy is a great starting point, but it should not be the endpoint for New York. For example, CHIA offers little information about home care or long-term care other than nursing home data. Given the importance of home care and personal care to the healthcare delivery system in New York, the New York equivalent of CHIA data and information should include relevant information on these topics, such as personal care services utilization through Licensed Home Care Services Agencies (LHCSA’s) and Consumer Directed Personal Assistance Services (CDPAS) providers, along with subsets of the data including stratification by acuity and hours of service per week.

It should be noted that New York already captures much of the data included in the CHIA taxonomy and makes many of these statistics publicly available.1 Still, even these data are not presented in a single location or within a user-friendly format. Our initial Policy Brief included a crosswalk of the healthcare data sets and information publicly available in Massachusetts compared to those publicly available in New York. An important implication of the fact that much of this healthcare delivery and payment system is already collected is that a dedicated State entity would not be starting from scratch to aggregate and synthesize this information and then present it in a coherent, usable way.

Data and Information Related to Patients, Providers, and Populations Served by Specific Providers or Payers

A second category of health data and information is related to patients, providers, and populations served by specific providers or payers, as captured through clinical encounter health information systems such as electronic health records and health information networks. This category of information includes information necessary to optimize the management of specific populations, such as individuals with complex, cross-sector needs and those attributed to specific providers or payers as part of an alternative payment model. Collecting and having user-friendly access to this type of health data and information is important for integrating clinical care across physical and behavioral health settings for individuals and specific patient populations.

In contrast to healthcare delivery system data and information, which is not patient-specific and is retrospective, this second category of data and information is comprised of patient-specific clinical data such as data from electronic health records (EHRs), remote patient monitoring, lab information systems, and other health information services systems. EHR data is transmitted from hospitals and other participating clinical providers to the State Health Information Network of New York’s (SHIN-NY) regional health information organizations (RHIOs), also known as Qualified Entities (QEs).

Policy recommendations with respect to this category of data and information include addressing existing challenges with the SHIN-NY's ability to synthesize and interpret health data on a statewide basis, given that this clinical information flows to the QEs already. Such policies should lead to greater centralization of the SHIN-NY's health information exchange (HIE) function, which will provide the opportunity to better link data related to clinical status with data related to service delivery. For example, if permissions and consent were granted to allow the New York eHealth Collaborative (NYeC), the SHIN-NY’s parent entity, to incorporate data such as Medicaid claims, prescription information, and perhaps even health-related human services data to enhance the existing clinical data flows, there would be significant value for patients, clinicians, and specific populations.

In addition to improving the ability to analyze specific populations, enhancing this data layer is important for other programmatic goals of NYS DOH and the State, including expanding alternative payment methodologies and global budgeting at the regional and health system levels. For example, this report from Milbank Memorial Fund demonstrates the value to patients and providers of utilizing a mature HIE platform in managing a targeted population. Specifically, the Report explains that,

A health information exchange (HIE) platform collects, organizes, and stores medical data from various providers within a geographical region on a centralized or decentralized database. HIE participants with appropriate authorizations can then access the medical data of patients with their consent. Digitally mature and well-functioning HIE platforms are well equipped to provide their members with the information services necessary to excel in all key areas of the CPC+ program.

HEALTHeLINK, the HIE in the setting studied in this report, is a well-established, widely adopted HIE platform that has been operating in the region since 2006. The long history of HEALTHeLINK, combined with its high adoption rate in the region, gives it a unique opportunity to consolidate comprehensive medical data of patients in western New York. Such wealth of data, coupled with state-of-the-art analytics, allows HEALTHeLINK to develop digital capabilities for population health management monitoring and control.

Improving the effectiveness of the SHIN-NY to produce meaningful, statewide health information would enable all types of providers connected to the SHIN-NY to operate with the same degree of visibility that is now achieved by individual health systems that use robust, integrated health information services systems in their inpatient and outpatient care.

Within mental health, the PSCYKES database of the NYS Office of Mental Health includes much of this critical data and information at the patient and claims level. One of the objectives for the State related to this part of the health data and information infrastructure should be a much more seamless sharing of data and information across different State agencies that also standardizes and aligns data definitions. Currently, physical health data managed by NYS DOH, and mental health, substance use, and OPWDD-related data managed by the “O” agencies (the Office of Mental Health, Office of Addiction Services and Supports, and the Office for People with Developmental Disabilities) are quite siloed, which interferes with the State’s goal of providing integrated clinical care.

Data and Information Related to Public Health and Social Determinants of Health for General Populations

A third category of health data and information relates to public health and social determinants of health for general populations, as captured through public health reporting, health-related human services reporting, and public surveys. The Prevention Agenda Dashboard is a good illustration of this type of population-wide data. While we understand that efforts are underway (as recently presented to NYS Public Health and Health Planning Council) to improve the collection and publication of public health data, we would argue that the biggest problem of the Prevention Agenda Dashboard and other public health data in the Department of Health, is that they are rarely used as an organizing principle for policymaking or program management. The Dashboard and the Community Health Assessment Clearinghouse include a wealth of underutilized public health data.

In thinking about the distinction between public health data and data supporting population health management, it is helpful to consider the “Three Buckets of Prevention,” as originally described by John Auerbach. The first bucket of prevention is clinical. These are preventive interventions provided in a one-on-one clinical setting and include, for example, recommended vaccinations, mammograms, or screening for tobacco use. The second bucket consists of preventive interventions provided outside of a clinical setting but still on behalf of identifiable individuals, for example, programs related to modifying home environments for individuals with asthma, or programs focused on individuals who are pre-diabetic. The third bucket of prevention consists of interventions related to the total population or community. These involve, “interventions that are no longer oriented to a single patient or all of the patients within a practice or even all patients covered by a certain insurer. Rather, the target is an entire population or subpopulation usually identified by a geographic area.”2

Regional public health information involves the type of data relevant to this third bucket. Common Ground Health in Rochester is an excellent example of a region in the State that engages in robust, data-supported regional health planning. Common Ground Health and its predecessor organization, the Finger Lakes Health Planning Agency, have been doing regional health planning for decades. A review of their website gives an illustration of what a good model looks like. There are other examples in New York, including the Adirondack Health Institute, and the Fort Drum Regional Health Planning Organization. Hospitals, too, analyze data from this third bucket of prevention as they develop their community health needs assessments, as required by the NYS DOH every five years. These assessments are available on hospital websites. For example, here is NYC Health + Hospital’s 2022 Community Health Needs Assessment.

Data and Information Related to Consumer Empowerment

Consumer-facing data and health information such as such as those related to price transparency, individual cost-sharing, quality of care across plans, and provider accessibility is sufficiently distinct in its purpose that it should be considered a separate category. Improving consumer-facing health information as part of a broader initiative to empower consumers in better managing their healthcare choices and expenditures is a significant opportunity that remains largely untapped in New York.

Price transparency is the area of consumer-facing health information for which there has been the greatest demand over the years. The 2020 New York State of the State called for a healthcare price comparison tool, which superseded previous efforts to require commercial insurance plans, through NYS Department of Financial Services (DFS) regulation, to develop such a tool for their members. The recommendations for the price comparison tool were included in the New York State Department of Health Price Methodology Workgroup’s Final Recommendations Report dated April 6, 2021. A rollout of the “NY Healthcare Compare” website is still a “coming attraction” on the DOH website.

We think that “consumer empowerment” is going to be an increasingly important trend in healthcare in the years ahead. Consumer-facing data and information will be a key component. Although the price transparency tool will be the most visible advance consumer-facing data, some consumer-facing data already exists. For example, there is information on individual cost-sharing within the NY State of Health tool for comparing plans and estimating costs. There are also resources available for comparing the quality of care across different payers. The Managed Care Reports available on the NYS DOH website are intended to assist in selecting health plans and the accompanying dashboard is helpful in facilitating individualized searches related to quality measures. The NYS Provider & Health Plan Look-Up tool is intended to assist consumers looking for a provider or hospital that works with their insurance plan.

A key point, which also applies to the other categories of data and information, is that a robust data and information infrastructure is a virtuous cycle. The more transparent, user-friendly, and comprehensive the data are, the more likely they are to be utilized. With greater utilization, gaps will become more apparent and can be addressed, making the data and information ecosystem even more robust.

Recommendations

Each of these four categories of data and information faces different challenges and requires different policy prescriptions for improvement. Since the Democratization of Health Data, Information and Policy Analysis Policy Brief focused primarily on the data and information infrastructure for the healthcare delivery and payment system, its central recommendation would most immediately affect that aspect of this overarching problem.

Our recommendation was that New York State should establish an Executive Branch Office of Health, Behavioral Health, and Social Determinants of Health Data Information and Analysis. The Office would have a mandate to gather this data and information from the relevant State regulatory agencies and synthesize the information to present a comprehensive picture of the healthcare delivery and payment system in New York. The extent of collection and publication of health data and reporting of health information should be at a level that is at least as comprehensive as data and information published by best practice states such as Massachusetts (through its Center for Health Information and Analysis). Because health, behavioral health, and social determinants of health increasingly need to be delivered in an integrated fashion, the Office would work to promote data and information exchange among the silos that exist today among DOH, the “O” agencies (OMH, OASAS, and OPWDD), and the Department of Financial Services.

Proposing an executive-level Office would also present an opportunity to establish a culture of integration in New York government that is desperately needed across the multiple silos that affect the healthcare delivery and payment system. The current lack of integration and the negative effects of the State’s existing silos should also be an issue that Governor Hochul’s newly formed Commission on the Future of Healthcare reviews over the next two years, given that the future of healthcare requires greater integration of these various parts of the healthcare system.

The challenge of improving the second category – “data and information related to patients, providers, and populations served by specific providers or payers” – is more complicated because of the technical, as well as policy challenges, raised by working with clinical encounter health information systems. It will probably take the better part of a year to develop a comprehensive roadmap for reform in New York. Our next Brief in this series on Health Data and Information will offer more background on these challenges and offer a “strawman case” for reforms that the State and healthcare stakeholders should consider.

1 For example, Emergency Department Visits in NYS, Volume and Estimated Cost of Hospital Services, All Payer Hospital Inpatient Discharges by Facility, NYSOH Enrollment Data, NYS Enrollment Databook, All Payer Inpatient Major Potentially Preventable Complication (PPC) Rates by Hospitals.

2 Auerbach J. The 3 Buckets of Prevention. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016 May-Jun;22(3):215-8. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000381. PMID: 26726758; PMCID: PMC5558207