Key Takeaways

The intersection of recent federal healthcare and immigration policy changes will have a significant impact not only on the recipients of government-funded healthcare services and on non-U.S. citizens residing in New York, but also on the immigrants who comprise New York’s healthcare workforce.

Legally present immigrants face new pressures related to accessing health insurance and/or the loss of protected status, and naturalized citizens may fear for family members who could be detained or deported

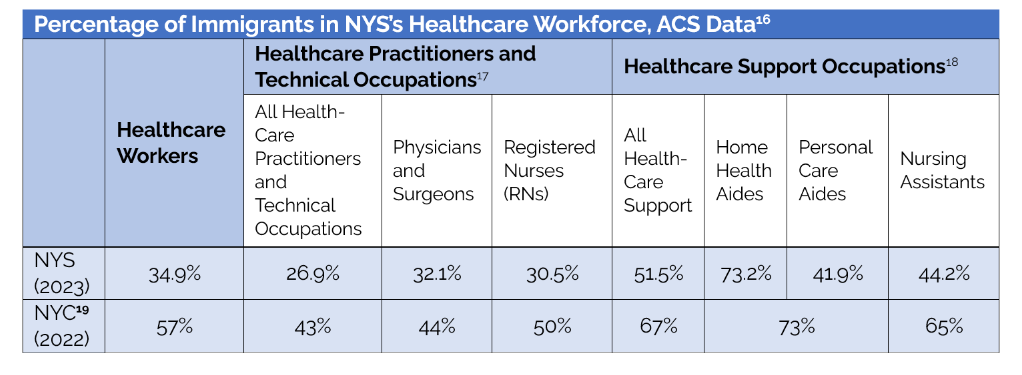

In 2023, 34.9% of the NYS healthcare workforce were immigrants, and in 2022, 57% of NYC’s healthcare workforce were immigrants.

In 2022, 73% of NYC’s home health aide and personal care aide workforce, combined, were immigrants, and across the State in 2023, 73.2% of home health aides and 41.9% of personal care aides were immigrants.

These healthcare workers not only provide services for many of New York’s Medicaid members, but they themselves may also be Medicaid beneficiaries.

In NYC, more than half of home health aides and personal care aides have Medicaid coverage, which may now be at risk, depending on their immigration status.

In 2023, 32.1% and 30.5% of physicians and RNs, respectively, in NYS, were immigrants.

In 2025, of the 5,094 applicants placed into physician residency training programs in NYS, 24.7% were non-U.S. citizens who attended an international medical school.

Recent shifts threaten to strip billions of dollars from the state’s healthcare funding, disrupt health insurance coverage for over one million residents, and erode supplemental food and housing supports—key social drivers of health.

These changes coincide with an already serious workforce shortage that is expected to worsen under new federal immigration policies.

Introduction

New York is facing an convergence of crises in its healthcare delivery system: federal changes that could result in the loss of billions of dollars to the system; loss of health insurance coverage for more than one and a half million New Yorkers;[i] loss of supplemental food benefits;[ii] potential loss of housing support[iii] (food and housing are important social drivers of health); a significant existing and growing health workforce shortage that will likely be worsened by the recent changes in federal immigration policy; and a strained primary care and rural health infrastructure, among others. The intersection of recent federal healthcare and immigration policy changes will have a significant impact not only on the recipients of government-funded healthcare services and on non-U.S. citizens residing in New York, but also on the immigrants who comprise New York’s healthcare workforce and the sustainability of our systems of care.

Drastic policy shifts to the health and social safety net enacted in H.R.1 - One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) not only impact the health, insurance coverage, and access to care for immigrants of all categories, but when coupled with sweeping shifts in immigration policy that have emerged from the Trump administration, the negative impact is compounded. Immigrants,[iv] who represent an important and significant portion of New York’s healthcare workforce, will face increased challenges to remain in the U.S. To put a finer point on the issue of access to care just mentioned, all New Yorkers, regardless of immigration status or health insurance coverage, could experience difficulties accessing care due to the widespread impact of decreases in hospital payments and increases in uncompensated care.

According to Gov. Hochul’s press release on July 11, 2025, “[m]ore than 2 million New Yorkers will lose their current insurance coverage, including approximately 730,000 lawfully-present non-citizens who could lose Essential Plan (EP) coverage[v] as over half of EP's budget — $7.5 billion in federal funding — is eliminated, and a further 1.3 million New Yorkers who will lose Medicaid coverage due to new eligibility and verification hurdles.” Some of these individuals may in fact be able to remain in the Essential Plan under different provisions, and presumably, some could receive State-only Medicaid. However, the OBBBA also changes the definition of an immigrant “qualified” to be eligible for Medicaid, Child Health Plus, and Medicare[vi] to exclude “refugees, asylees, parolees, persons in temporary protected status, and other previously recognized categories,” and also “[p]rohibits enhanced federal funds from being applied, where applicable (adults 0-138 percent of the federal poverty limit in New York State)”[vii].

Immigration Policy

The efforts of the Trump Administration to make it more difficult for immigrants to access healthcare services, even when they are present legally is part of a broader effort characterized by “mass deportations, challenging birthright citizenship, and ending temporary protected status for hundreds of thousands of immigrants.”[viii]

As described by the New York City Bar Association, which has been tracking the administration’s actions related to non-citizens, among others:

“President Donald J. Trump has acted quickly on his campaign promise to focus on immigration, including aggressively pursuing removal of noncitizens, pressuring states and localities to cooperate in immigration enforcement, limiting access to humanitarian forms of relief, and closing the southern border, to name just a few actions to date. Through a series of executive orders (EO), policy memoranda, and other actions, the administration is taking major steps to reshape immigration policy and practice that test the limits of executive power.”

The tactics of the Trump administration in implementing its “aggressive removal of non-citizens” depart from what have been described as “long-standing practices.”[ix] These new tactics include early revocation of temporary protected status designations; revoking “protected area” determinations related to enforcement activities for places such as healthcare facilities, schools, places of worship, or social service sites;[x] arresting individuals when they present at immigration courts; utilizing data collected by federal agencies for other purposes, for immigration enforcement; invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 which is a presidential wartime authority; and arbitrarily revoking visas, among others.[xi]

Immigrants are essential to the nation’s workforce and contribute to the economy in significant ways, including by paying taxes.[xii] The chilling effects of the current administration’s policies and practices related to non-US citizens could be significant. Per the Brookings Institution:

“We have argued elsewhere that the high levels of immigration boosted labor force growth and aided in the post-COVID-19 economic recovery. The significant decline in net immigration flows which will occur this year, possibly yielding net negative migration for the first time in decades, will reduce GDP growth and could contribute to a recession. Certain immigrant-dependent industries like agriculture, construction, and services may see labor shortages. Slowing immigration also adds to concerns about the Social Security Trust Fund which is expected to be exhausted in 2035.”[xiii]

Immigrants in the Healthcare Workforce

U.S. Hospital Workforce

The very real impacts of the healthcare and immigration policy changes discussed above, impacting both undocumented and lawfully present immigrants, will lead to a forced as well as voluntary outflow of all categories of immigrants and will likely result in a decrease in future immigration to the U.S. Legally present immigrants face new pressures related to accessing health insurance and or the loss of protected status, and naturalized citizens may fear for family members who could be detained or deported.[xiv]

An analysis by KFF of the 2023 CMS American Community Survey data indicate that nationally, approximately one in six hospital workers (clinical and non-clinical) were immigrants. Per KFF, “[m]ost immigrant hospital workers are citizens (74%), but about a quarter are noncitizen immigrants (26%). Among clinical hospital occupations, the data show:

In New York, 29 percent of all hospital workers in 2023 were immigrants. In fact, New York was one of nine states in which “at least one fifth of hospital workers”[xv] were immigrants.

New York’s Healthcare Workforce

Immigrants constitute an important and significant portion of New York’s healthcare workforce. In 2023, 34.9 percent of the New York State healthcare workforce were immigrants. In 2022, 57 percent of New York City’s healthcare workforce were immigrants.

Homecare

Seventy-three percent of New York City’s 2022 home health aide and personal care aide workforce, combined, were immigrants. Across the State in 2023, 73.2 percent of home health aides and 41.9 percent of personal care aides were immigrants. These healthcare workers not only provide home-based services for many of New York’s Medicaid members, but they themselves may also be Medicaid beneficiaries. In New York City, more than half of home health aides and personal care aides are covered by Medicaid,[xx] and their Medicaid coverage may now be at risk, depending on their immigration status.

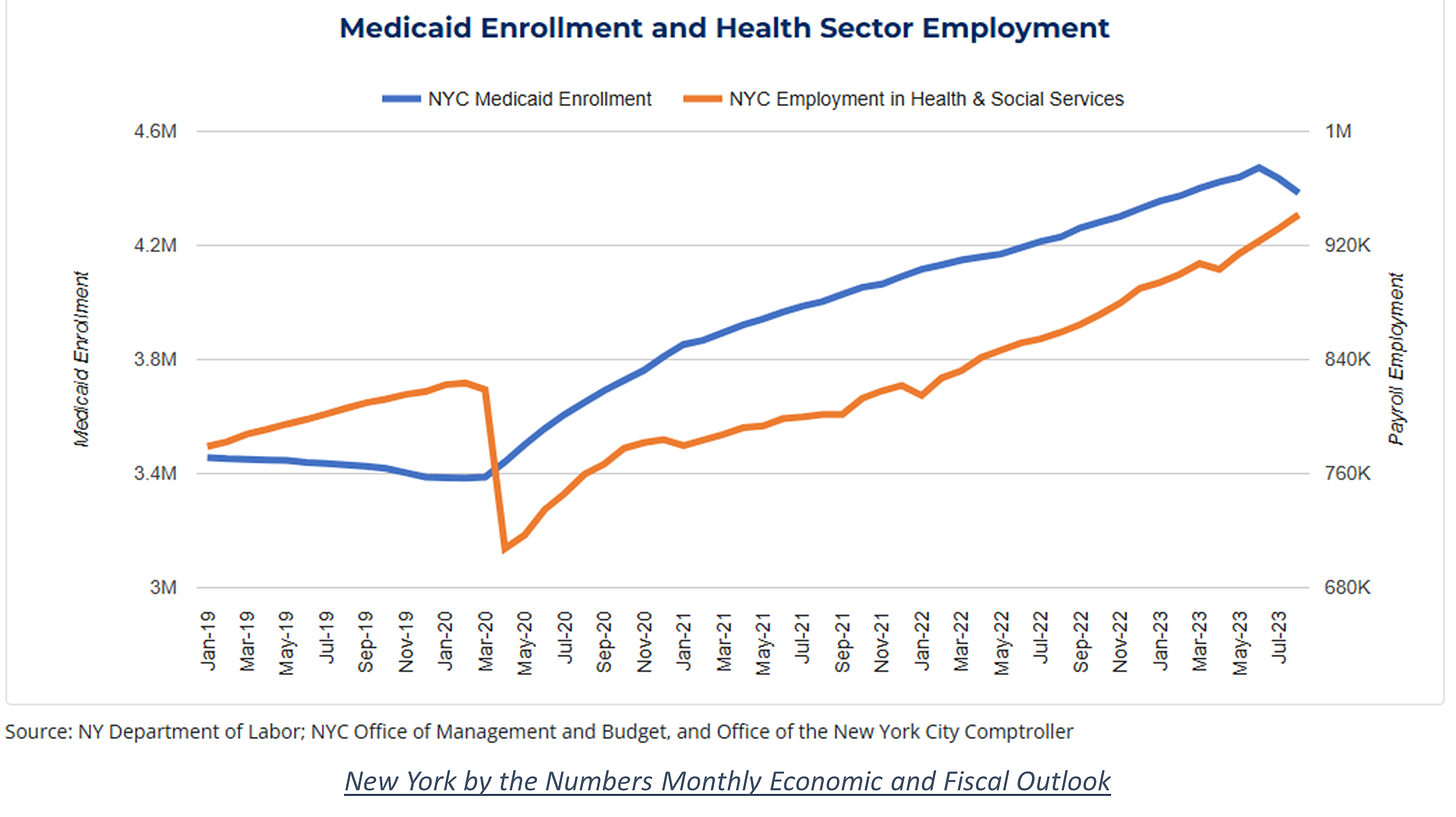

It may seem intuitive but it is nevertheless striking, as depicted in the graph below, that there is a direct relationship between the growth of Medicaid enrollment in NYC and the growth of health and social services sector employment in NYC.

Much of this enrollment growth has occurred since 2020, due in part to the federal maintenance of effort requirements on states’ Medicaid eligibility tied to the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency and in part to the expansion of New York’s Medicaid long-term care services, including access to homecare and personal care services. Growth in Medicaid enrollment and spending on home care and personal care long-term care services has been significant over the last dozen years, as the Step Two Policy Project has examined on several occasions.[xxi],[xxii] This growth has not only been in services, though, but has also led to a significant expansion of the home health and personal care aide workforce.

Per an analysis by Bill Hammond from the Empire Center, the “state’s workforce of home health and personal care aides grew to an estimated 623,000 as of May 2024, according to BLS’s Occupational and Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics,” and the “state’s one-year increase of 57,000 [between 2023 and 2024] accounted for almost a fifth of the home health aide jobs added nationwide.” As mentioned earlier, many of these lower-paid, healthcare support occupations are performed by immigrants, many of whom are themselves, Medicaid beneficiaries.

Hospitals

The Importance of Non-U.S. Citizen International Medical Graduates to New York’s Hospitals

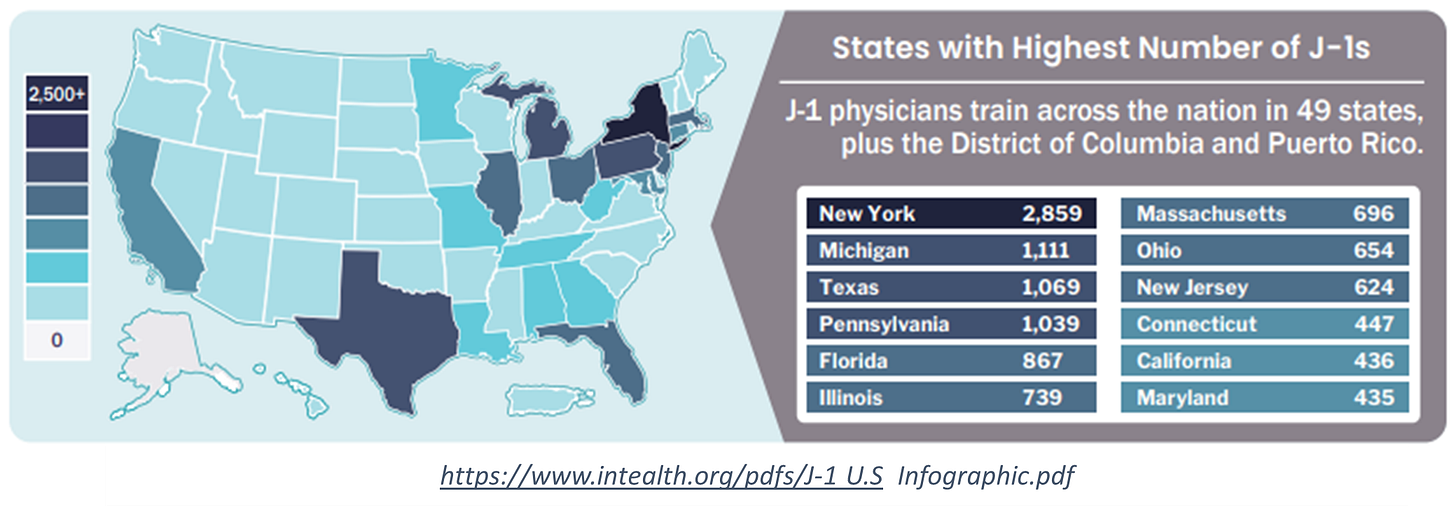

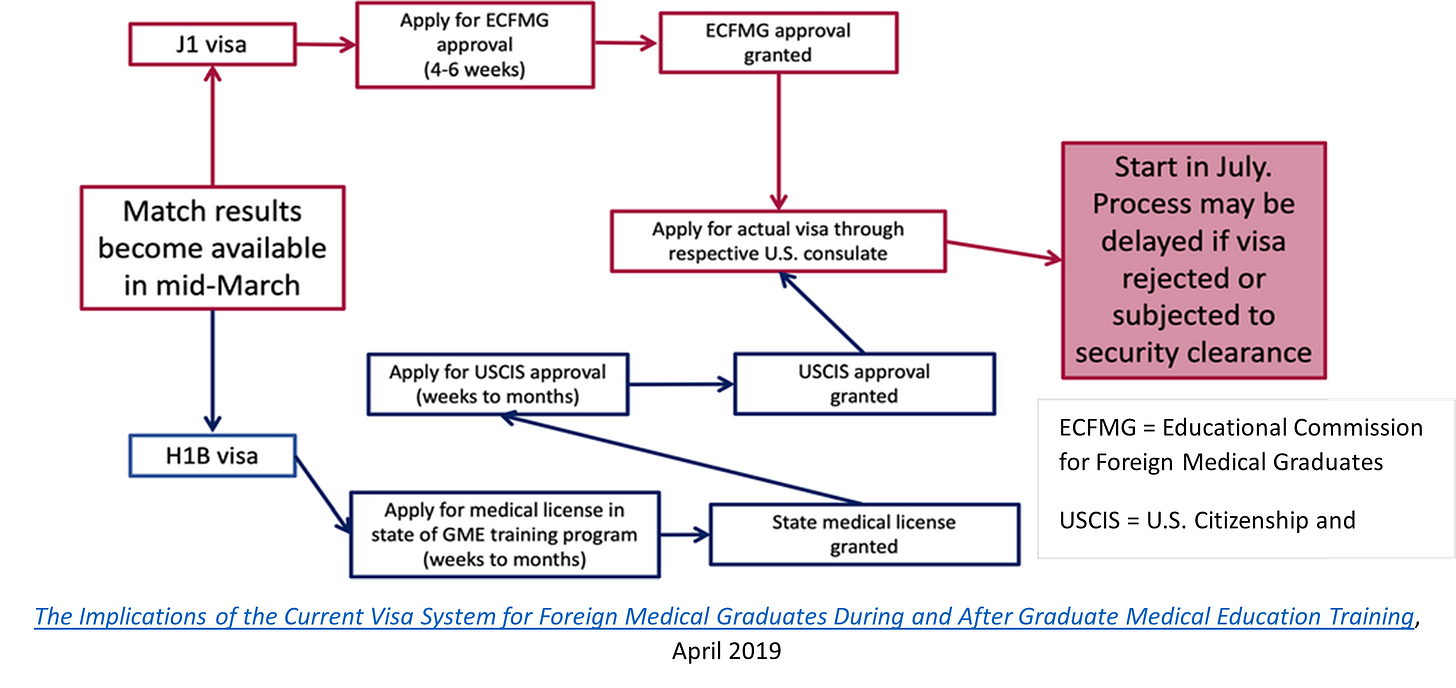

Nationally, approximately 27 percent of all physicians in hospitals are immigrants – about 19 percent are naturalized citizens and about 8 percent are non-citizen immigrants.[xxiii] Each year, thousands of international medical graduates (IMGs) are matched into U.S. residency and fellowship programs, a required step before they can become licensed to practice independently in the U.S. In some cases, IMGs have already been practicing physicians in their home country, but in order to practice in the U.S., they must also complete a U.S.-based residency program. Most of the non-U.S. citizen IMGs enter the U.S. through the J-1 visa program, which involves program sponsors, and the participants are considered to be “nonimmigrants.”[xxiv] These physicians represent not only an important inflow to the workforce, but also a critical mechanism for staffing hospitals in underserved areas, including rural areas, and in underfilled specialty programs.

In 2025, of the 5,094 applicants placed into residency training programs in NYS, 24.7 percent were non-U.S. citizens who attended an international medical school (non-U.S. IMGs). And of the 1,519 applicants placed into specialty fellowship training programs in NYS, 22.2 percent were non-U.S. IMGs.[xxv]

The graphic below identifies the states with the highest number of J-1 visa physicians currently in training (i.e., in any year of a residency or fellowship program), which is a cumulative perspective.

Non-U.S. IMGs must obtain visas to enter graduate medical education (GME) training programs – the two primary visa programs for physicians are the J-1, mentioned earlier, and the H-1B. These physicians typically enter the U.S. on J-1 visas, a process facilitated by the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG), which evaluates the clinical and communication skills of IMGs and certifies them for training programs.

Visa Policy Changes Disrupt the Physician Pipeline

Following the President’s recent Proclamation restricting entry to the U.S. for certain foreign nationals and changing policies for multiple visa programs, there are now disruptions in the flow of international medical graduates (IMGs) due to federal visa restrictions. The core issue was the suspension of J-1 visa interview appointments (and thus approvals), which is the primary visa pathway for thousands of foreign-trained physicians entering U.S. residency programs each year.

On May 27, 2025, the Trump administration paused the scheduling of interviews for several types of visa applicants, including those physicians applying for J-1 visas, with the stated purpose of introducing enhanced vetting procedures. The pause was lifted on June 18, 2025, with the State Department announcing “… all applicants for F, M, and J nonimmigrant visas will be instructed to adjust the privacy settings on all of their social media profiles to ‘public’.”[xxvi]

Then, on June 4, 2025, the Trump administration’s Proclamation titled, RESTRICTING THE ENTRY OF FOREIGN NATIONALS TO PROTECT THE UNITED STATES FROM FOREIGN TERRORISTS AND OTHER NATIONAL SECURITY AND PUBLIC SAFETY THREATS [sic], fully suspended and limited entry to a case-by-case basis to the U.S., of nationals from the following countries: Afghanistan, Burma, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Haiti, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen. The Proclamation also established a “partial suspension of entry” for nationals from Burundi, Cuba, Laos, Sierra Leone, Togo, Turkmenistan, and Venezuela.

Medical residencies in the U.S. traditionally begin on July 1, with orientation programs starting in June. Without timely visa approvals, incoming residents may not arrive in time to begin training. Since these first-year residents play critical clinical roles—providing direct care and easing workload burdens for more senior physicians, their absence could disrupt staffing models in hospitals already stretched thin.

States often struggle to recruit U.S.-trained physicians to serve in their rural communities, making IMGs essential to maintaining basic healthcare services. Many residency programs in rural areas or specialties that experience consistent shortages, such as family medicine, pediatrics, and geriatrics, increasingly depend on IMGs.

The pause in visa interview appointments resulted in increased confusion and worry in an already fraught process for non-U.S. IMGs coming to New York for their residencies and fellowships. Although the outcome as of early July appears to be relative stability, with the exception of one or two academic medical centers still missing residents from nations on the new travel ban list and a few others that will have residents start late due to visa interview appointments scheduled far in the future.[xxvii] The impact during May and June, however, prior to the lifting of the interview pause, demonstrated just how important and vulnerable this component of the physician workforce is. Towards the end of June, after appointments for J-1 visa interviews had been restarted, NBC News published a report online explaining the situation nationally,

“[a] week before they are due to start work at U.S. hospitals, hundreds of doctors from abroad are still waiting to obtain visas granting them temporary stays in the country. … Many of them have been in limbo since late May, when the State Department suspended applications for J-1 visas, which allow people to come to the U.S. for exchange visitor programs.”

The report goes on to describe the importance of non-U.S. IMGs in staffing hospitals in rural and low-income areas that are designated as medically underserved, and explains the value, beyond filling vacancies, that these physicians bring,

“International doctors are often matched with hospitals in underserved communities in part because the positions are less coveted by U.S. applicants. But many international doctors also bring a unique skillset to neighborhoods — they speak languages other than English and may be familiar with diseases that aren’t common in the U.S.”

Impact on Graduates of Foreign Nursing Schools

The impact of shifts in immigration policy does not only affect the hospital physician workforce. Non-U.S. citizen registered nurses, pharmacists, and other licensed professionals are impacted by policy changes to visa programs, temporary protected status designations, and the expansion of immigration enforcement activities to previously protected areas, including healthcare facilities. These changes affect not only the individual, but their families as well.

For example, 64.8 percent of New York’s registered nurses (RNs) work in hospitals (inpatient, emergency department, and outpatient settings).[xxviii] In New York City, the percentage of registered nurses working in hospitals is 69.8.[xxix] And “the vast majority of hospitals [in New York] continue to experience RN recruitment and retention challenges, although many of these [NY] hospitals reported that the situation had improved.”[xxx] With 30.5 percent of the State’s overall RNs and 50% of the overall City’s RNs being non-U.S. citizens, however, the improvements in RN staffing levels reported by Chief Nursing Officers may prove to be short-lived.

The Office of Professions at the NYS Education Department (NYSED) is responsible for licensing nurses and establishes eligibility and requirements. For an RN who has graduated from a non-U.S. nursing school, as discussed earlier with IMGs, there are several steps that must be taken, including having their credentials evaluated and verified by an independent organization[xxxi] and obtaining lawful status to work in the U.S., before they can be licensed and practice. Unlike the process for non-U.S. IMGs, though, the J-1 visa program is not an option because foreign-born RNs are generally coming to the U.S. for employment, rather than graduate education. Therefore, RNs who have been recruited from abroad[xxxii] by U.S. hospital systems to help ease their staffing shortages, generally apply for employment-based immigration visas such as an EB-3 visa, intended for “a skilled worker, professional, or other worker” who meets the educational, training, and experience requirements and who has a full-time job offer from a U.S. employer.[xxxiii]

TruMerit, in its 2024 Nurse Migration Report, presents information based on data gathered from its visa (permanent green cards [e.g., EB-3 visa], Trade NAFTA [TN], and H1-B {only for advanced practice/education >4yrs]) and credentialing services.[xxxiv] They include a summary of changes occurring in the U.S. that is based on 2024 data, which predate the current federal administration’s policy shifts:

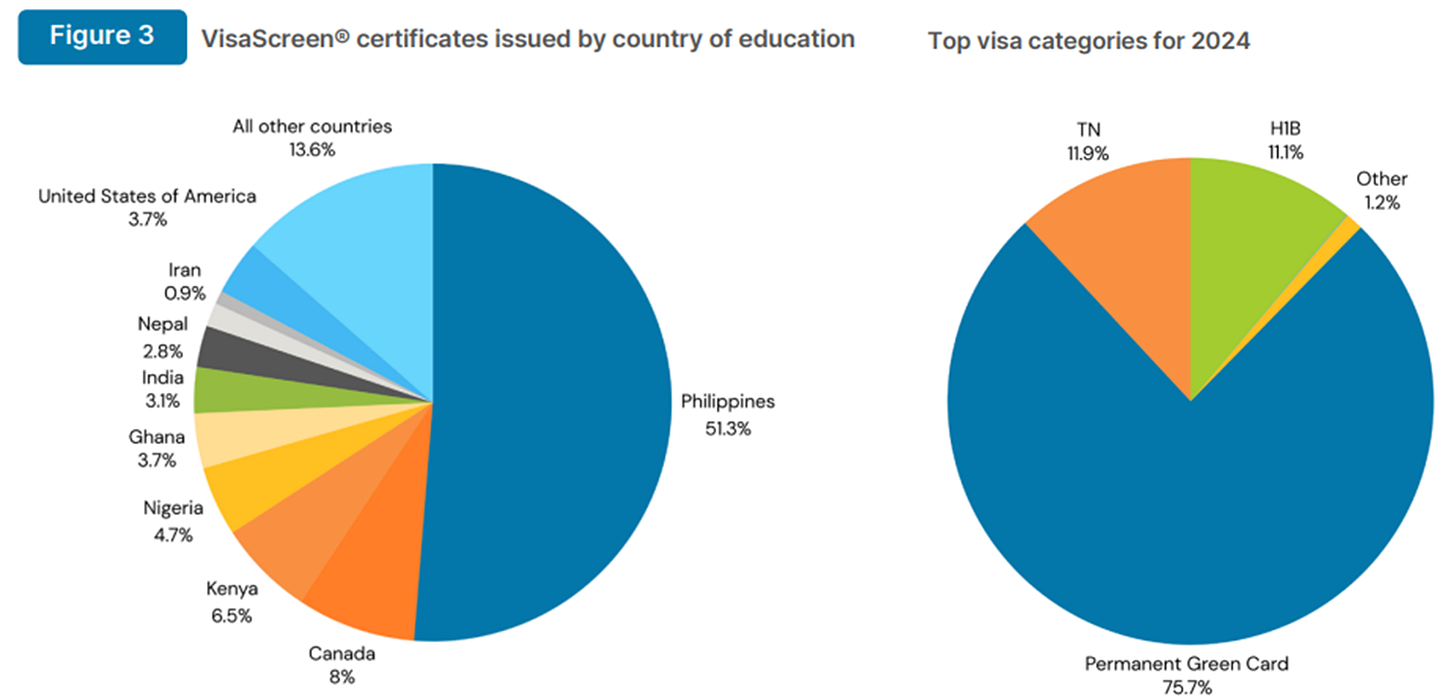

Eighty-six percent of the 2024 applicants for whom TruMerit provided visa and screening services (VisaScreen®) were RNs, 12 percent were clinical laboratory specialists, and the remaining two percent were other licensed healthcare professionals such as physical therapists, occupational therapists, audiologists, and others. The country of education and the top visa categories of the 2024 applicants were:

Of the top source countries for emigration, only Iran is included in the President’s list of restrictions on the entry of foreign nationals mentioned earlier. Regardless, delays in visa approvals, uncertainty for individuals and family members, even those who are authorized to be in the U.S., and robust global demand for nurses, coupled with efforts by source countries to retain their emigrating nurses, may present significant future barriers to addressing hospital workforce shortages in New York and nationwide by staffing with foreign-educated nurses.

Nursing Homes

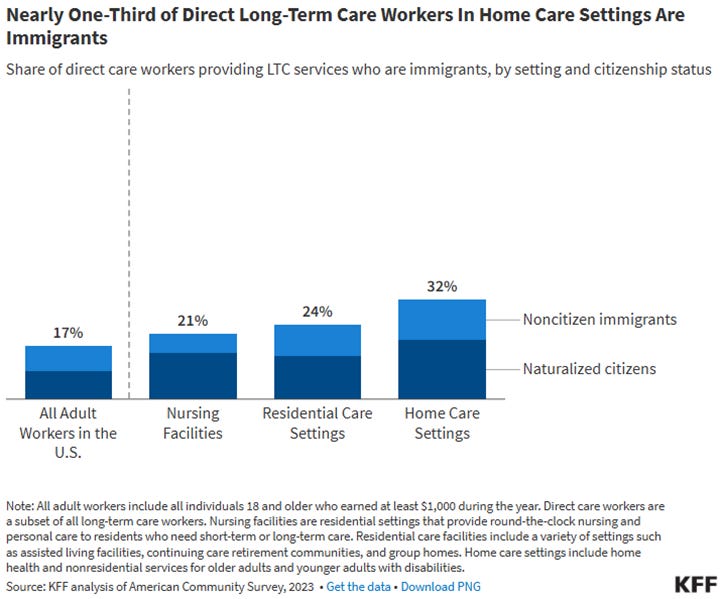

As presented earlier in this Issue Brief, immigrants (of all statuses) who are certified nursing assistants (CNA) comprise 44.2 percent of the State’s total and 65 percent of NYC’s total CNA workforce. Certified nursing assistants are an essential part of the nursing home workforce, working alongside registered nurses and licensed practical nurses and providing much of the daily direct care. As is the case in many hospitals, New York’s nursing homes are experiencing ongoing staffing shortages. The Trump administration’s new immigration policies related to terminating temporary protected status for certain nationals[xxxv] and allowing immigration enforcement activities to occur inside healthcare facilities, among other actions, have the potential to significantly disrupt the lives and livelihoods of immigrant CNAs, and to also impact resident care in nursing homes.

In July 2025, Newsday reported,

“Employees at elder care facilities on Long Island and across the state who have temporary protected status are receiving deportation letters from the Trump administration, putting already understaffed nursing homes and assisted living communities at risk of being unable to care for their most vulnerable residents, according to advocates and trade groups.”

KFF provided the following graphic depicting the composition of the long-term care workforce in the U.S. in terms of both setting and immigration status,

Conclusion

New York is experiencing a convergence of crises in its healthcare delivery system, driven by sweeping federal policy changes and longstanding structural challenges. Recent shifts threaten to strip billions of dollars from the state’s healthcare funding, disrupt health insurance coverage for over one million residents, and erode supplemental food and housing supports—key social drivers of health. These changes coincide with an already serious workforce shortage that is expected to worsen under new federal immigration policies. The intersection of healthcare and immigration policy reforms resulting from H.R.1, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, will resonate across the state, disrupting access to care not only for immigrants but for all New Yorkers, as hospitals face mounting uncompensated care costs and diminished resources.

These changes, coupled with a chilling effect on immigration, threaten the stability of New York’s healthcare workforce, a significant share of which are immigrants. The long-term care sector in particular, in both nursing homes and home care settings, may face a double impact in that the residents, patients, and the workers themselves may experience loss of health coverage, and may also experience the negative impacts of newly restrictive immigration policies and enforcement.

An important topic, but one we haven’t focused on in this Issue Brief is the moral dilemma related to the emigration of licensed professionals—such as physicians, nurses, and other health workers—from low and middle-income “source” countries to higher‑income “destination” countries. Wealthier nations benefit from the skills and training investments made by resource‑constrained countries, often exacerbating workforce shortages in places that may already struggle to meet their healthcare needs. This “brain drain” can undermine local health systems, deepen global inequities, and compromise access to care for vulnerable populations in source countries. At the same time, restrictive credentialing processes in destination countries often lead to “brain waste,” where migrant professionals work below their level of training. Balancing the right of individuals to seek opportunities with the responsibility to protect the health capacity of source countries remains a complex ethical dilemma in global health.[xxxvi]

Endnotes

[i] By the Numbers: The Republican ‘Big Ugly Bill’ Would Have Devastating Impacts on New York Health Care Providers, Patients, Employees and Communities, July 1, 2025.

[ii] Governor Hochul Unveils Devastating Impacts of Republicans’ ‘Big Ugly Bill’ on New York State, July 11, 2025.

[iii] Trump law boosts New York housing, but looming cuts could blow it up, July 9, 2025.

[iv] “Immigrants include noncitizen immigrants (both undocumented immigrants as well as those who legally reside in the US, including through a green card or a student or work visa) and naturalized citizens,” What Role Do Immigrants Play in the Hospital Workforce? KFF, June 17, 2025.

[v] Although a portion of this population, referred to as the Aliessa population, for whom the State is required to provide Medicaid benefits, will likely shift back to State-only Medicaid from the Essential Plan.

[vi] Including for those legally present immigrants who have worked in the U.S. and have paid into Medicare. (How the OBBBA undermines healthcare and harms America - Week of July 6 - July 12, 2025)

[vii] An Analysis of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA’s) Impact on Healthcare for New York, July 10, 2025.

[viii] Megabill Hits Health Care for Immigrants, Including Legal Ones, Hard, July 4, 2025.

[ix] 100 Days of Immigration Under the Second Trump Administration, Brookings, April 29, 2025.

[x] “The fundamental question is whether our enforcement action would restrain people from accessing the protected area to receive essential services or engage in essential activities. Our obligation to refrain, to the fullest extent possible, from conducting a law enforcement action in or near a protected area thus applies at all times and is not limited by hours or days of operation,” Guidelines for Enforcement Actions in or Near Protected Areas, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, October 27, 2021.

[xi] 100 Days of Immigration Under the Second Trump Administration, Brookings, April 29, 2025.

[xii] In New York, e.g., in 2023 immigrants paid $74.8 billion in taxes and contributed $160.5 billion in spending.

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] What Role Do Immigrants Play in the Hospital Workforce? KFF, June 17, 2025.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Custom Table - Dataset: ACS 1-Year Estimates Public Use Microdata Sample (2023); Columns = Nativity; Rows = Selected Geography NY and OCCP; Cell Value = Count; Weight = PUMS person weight; Vintage = 2023. United States Census Bureau.

[xvii] Chiropractors, Dentists, Dietitians and nutritionists, Optometrists, Pharmacists, Emergency medicine physicians, Radiologists, Other physicians, Surgeons, Physician assistants, Podiatrists, Audiologists, Occupational therapists, Physical therapists, Radiation therapists, Recreational therapists, Respiratory therapists, Speech-language pathologists, Exercise physiologists, Therapists all other, Veterinarians, Registered nurses, Nurse anesthetists, Nurse midwives, Nurse practitioners, Acupuncturists, Healthcare diagnosing or treating practitioners all other, Clinical laboratory technologists and technicians, Dental hygienists, Cardiovascular technologists and technicians, Diagnostic medical sonographers, Radiologic technologists and technicians, Magnetic resonance imaging technologists, Nuclear medicine technologists and medical dosimetrists, Emergency medical technicians, Paramedics, Pharmacy technicians, Psychiatric technicians, Surgical technologists, Veterinary technologists and technicians, Dietetic technicians and ophthalmic medical technicians, Licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses, Medical records specialists, Opticians, dispensing, Miscellaneous health technologists and technicians, Other healthcare practitioners and technical occupations, 2023 Code Lists, United States Census Bureau.

[xviii] Home health aides, Personal care aides, Nursing assistants, Orderlies and psychiatric aides, Occupational therapy assistants and aides, Physical therapist assistants and aides, Massage therapists, Dental assistants, Medical assistants, Medical transcriptionists, Pharmacy aides, Veterinary assistants and laboratory animal caretakers, Phlebotomists, Other healthcare support workers, 2023 Code Lists, United States Census Bureau.

[xix] 2022 CMS American Community Survey data from Essential But Ignored: Low-Earning Immigrant Healthcare Workers and their Role in the Health of New York City, Center for Migration Studies, January 31, 2025.

[xx] Essential But Ignored: Low-Earning Immigrant Healthcare Workers and their Role in the Health of New York City, Center for Migration Studies, January 31, 2025, page 2.

[xxi] Managed Long Term Care – Enrollment and Spending, Step Two Policy Project.

[xxii] A Review of the Managed Long-Term Care Issues in the FY 25 Executive Budget, Step Two Policy Project.

[xxiii] What Role Do Immigrants Play in the Hospital Workforce? KFF, June 17, 2025.

[xxiv] “The J-1 classification (exchange visitors) is authorized for those who intend to participate in an approved program for the purpose of teaching, instructing or lecturing, studying, observing, conducting research, consulting, demonstrating special skills, receiving training, or to receive graduate medical education or training.” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).

[xxv] 2025 Main Residency Snapshot, New York.

[xxvi] Announcement of Expanded Screening and Vetting for Visa Applicants, U.S. Department of State, June 18, 2025.

[xxvii] Personal communication.

[xxviii] Understanding and Responding to Registered Nursing Shortages in Acute Care Hospitals in New York, Center for Health Workforce Studies, 2024.

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] Ibid.

[xxxi] RNs seeking licensure in NYS are not required to use TruMerit, previously called the Commission on Graduates of Foreign Nursing Schools (CGFNS), but it is recommended by NYSED.

[xxxii] Nursing Shortage Intensifies Due to Immigration Policies, ABC News, June 9, 2025.

[xxxiii] Employment-Based Immigration: Third Preference EB-3, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).

[xxxiv] “While the data within this report are not a comprehensive representation of all foreign educated healthcare professionals coming into the U.S. in 2023, they are nonetheless valuable as a limited proxy in the absence of a national tracking system,” TruMerit, 2024 Nurse Migration Report, p. 9.

[xxxv] Including from Haiti, Honduras, and others - Temporary Protected Status, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

[xxxvi] Growing Health Worker Migration to the U.S. and U.K. Raises Fairness and Training Issues, Penn Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, May 1, 2024.